Mars has two moons, Phobos and Deimos. A solar day on the Red Planet is approximately twenty-four hours, thirty-five minutes, and thirty-five seconds long. There are volcanoes, dust devils, and liquid water. Once every two years, Mars and Earth are closest to each other when they are on the same side of the Sun. Elon Musk often speaks of reaching Mars in his lifetime. But when I think of Mars, I think of my father.

Before he died in 2006, my father asked me for feedback on a draft of his memoir My Life in the Aerospace Electronics Business. I knew nothing about aerospace electronics or electrical engineering. To him it didn’t matter. I happened to be visiting from the Bay Area that summer. Up until that point, I knew my father spent every morning outside on the patio in his blue terry cloth robe, chain-smoking Marlboros and filling in the LA Times crossword puzzle. I was enthusiastic when he told me about his project. He was in his early seventies, bored, and mad about not working anymore. Big Ed (the nickname given to him by my aunties), had earned his PhD in electrical engineering while working in the defense industry. A part-time job teaching electronic circuits eventually led to becoming dean of engineering at Pacific States University. Heading a department was still part-time (evenings and weekends) while he project managed attack missile systems and planetary probes. Work should have been my father’s nickname.

One afternoon he asked me to drive him to Kinkos to make copies of his manuscript. Before we left the house, he handed me a lean pile of typewritten pages sprinkled with typographical carets, cross-outs, and stet instructions. Included with the IBM Selectric pages were half a dozen Xeroxed copies of photographs labeled with sticky notes, and a hand-drawn chart entitled the Art of Miscommunication. Okay, I said. Was this the beginning? No, he replied. This was it. The entirety of a life boiled down to the length of an engineering proposal, I thought.

I needed to be tender. My father was trusting me to read his work. I hadn’t published a book, so I had no clue about process. But I understood adaptive transformations. I had earned a bachelor’s in fine arts on the five-year plan after dumping psychology, pragmatically followed by an MBA and a job in corporate financial planning and analysis. Now, I was a new poet who had switched my MFA creative writing concentration to playwriting midstream.

Providing feedback in a writing workshop for some is a blood sport. Sharing suggestions with a parent was different. The fact that my mother and siblings apparently had misgivings about his commitment to writing was the main reason to tread lightly. But it was clear in the way my father thanked me as the Kinko’s clerk placed his slim volume in a kraft bag, that my input meant a lot to him.

Prior to reading his manuscript, I knew very little about the details of my father’s youth. I’ve never seen a picture of my father’s father or his step-father. I had no idea he had intended to be a civil engineer, but it made sense given his engineering battalion experience during the Korean War as a teenager. We lived in Southern California, a defense contractor and aerospace hub. My father eventually had a security clearance. I remember my parents talked about his trips to Edwards and Eglin air force bases. There is an element I suppose, in everyone’s professional journey of being in the right place at the right time. As Elon Musk undoubtedly knows, right place right time is especially true for a successful mission to Mars.

Looking back at old Polaroids from the sixties, I’d often be the only one in family photos with my fist in the air. As a first grader, I didn’t fully understand the Vietnam War, but I was on the side of anti-war protestors and the Black Panther Party. Hah, an activist at six! By the time I was twelve, my political views were fully formed and informed. I supported Shirley Chisolm for president; I did not support the Vietnam War or the military-industrial complex, which put me at odds with how my father supported us. I was vocal about it. He kept his feelings about my adolescent outrage to himself.

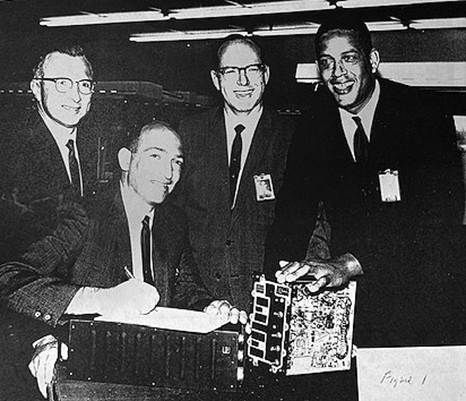

My father’s engineering discipline was guidance, navigation, and control. One of the photos in My Life in the Aerospace Electronics Business documents the hand-off of a bearing and range computer indicator for Grumman’s A-6A attack aircraft, which was used in the Vietnam War. My father is smiling with colleagues, his large left hand resting on his company’s special equipment for their photo op. But as I learned from his manuscript, my father’s professional success hadn’t been linear.

I read my father’s parents divorced—possibly during the Great Depression or at the beginning of World War II. The exact year is unclear as were many facets of his life. My grandmother remarried and had another son sometime in the early forties. That marriage didn’t last either. I know my grandmother spent a decade in a sanitarium due to tuberculosis. There is no mention of Nana’s illness in my father’s manuscript, as if a switch was flipped. My great-grandmother filled the void of a missing mother, father, and step-father. From what I can piece together, in September of 1945 my father started junior high school as World War II was coming to an end. The next year he had gotten a paper route; he described his job as a new beginning. Unfortunately, he was caught stealing donuts on the route and spent a month in juvenile hall.

Big Ed was six-foot-four. I have no idea when he hit that height. He wrote he had enlisted in the California National Guard as a tenth-grader. By the time the Korean War broke out, he was two months shy of his 17th birthday—the eligible age for enlistment. It’s hard to envision this happening in the twenty-first century. But my father was a kid of the Great Depression, who viewed his home life as shaky, and saw the California National Guard, which was segregated at the time, as just another part-time job. He had only expected to “soldier” on the weekends. In 1950, my father served in the segregated 1401st Engineer Combat Battalion stateside. The G.I. bill assisted with his college education after an honorable discharge, and ultimately helped him buy his first house. Lying about his age was his ticket into the middle class.

Photo credit collection of the author.

I didn’t need to read My Life in the Aerospace Electronics Business to know that my father was assigned to NASA’s Viking Lander project—literally the search for life on Mars. Mars during that time was a big part of my family’s life. His company was one of three government contractors responsible for delivery of the gas chromatograph mass spectrometer (GCMS), an instrument intended to test Martian soil. In case studies, it has been documented that the GCMS project had suffered from fiscal, technical, and management issues. To solve for coordination issues, my father’s company was ultimately assigned as prime contractor. Reading NASA’s published account in Searching for Life on Mars: The Development of the Viking Gas Chromatograph Mass Spectrometer (GCMS) is fascinating when juxtaposed against my father’s personal experience.

Photo credit collection of the author.

They didn’t find it. Life. Water. Not in the seventies. But “we’ve” never stopped trying.

Elon Musk wants to colonize Mars with SpaceX, he says, to save humanity by becoming a “spacefaring” civilization. However, Musk’s aspiration seeps of adventure tourism mixed with competitive avarice. A call-to-action button is available on SpaceX’s website for future Mars, Moon, Space Station, and Earth Orbit missions. The inquiry forms include a Yes/No response to financial qualification, and a message that all fields are required (including the country of one’s passport.) SpaceX tee-shirts, hoodies, patches, and wall decals for adults and children can be purchased on the site. Elegantly designed intravehicular (IVA) and extravehicular (EVA) suits can be explored. On the other hand, despite the performative style of Musk, the performance of SpaceX cannot be denied. Exhibit A—a SpaceX Dragon capsule was used to retrieve two stranded astronauts on the International Space Station and deliver a new crew.

In my work, I haven’t stopped writing about Mars. For me, Mars is an extended metaphor, operating in part like an easter egg. My father once told me jazz is math and math is God. In my work, Mars is hope and hope is life. Mars is a jazz riff played in the musical key signatures of F and G. A former poetry teacher described my work to me as distant. Perhaps the feedback was in response to my tendency to use or misuse the language of science and aerospace as stand-ins for commonly used poetic tropes. I chose not to respond to my teacher’s comment. Although I thought, I can explain it to you, but I can’t understand it for you.

On average, Mars is 140 million miles away from Earth. On August 20, 1975, Viking I was launched from Cape Canaveral, to be followed by Viking II on September 9, 1975. Beaming with pride as a self-described activist teenager, I was relieved my father’s multiyear involvement on the Viking project did not entail guiding missiles from planes or navigation systems for naval aircraft carriers. The instrument my father helped build is in the collection of the Smithsonian’s National Air and Space Museum. SpaceX may very well be next. The way I see it, Edward Nathaniel Jackson (an African American aerospace engineer born and raised in Black Los Angeles during the thirties) has already got there.

*

from Orbiter

My tongue like spongy rock (bone to dune field) Phobos & Deimos pocked by impact.

A determined body can be repurposed.

A body can be changed. 687 earth days

sockets & pebbles, pitch & yaw, striations

of abandonment lay circumpolar.

Though you’re gone, Sojourner still roves as scientists blow Amens. Thirty years probing Aeolian winds. If only this crust could stop leaching—

Valles Marineris is a canyon I can’t scale.

Mars reminds me of you.